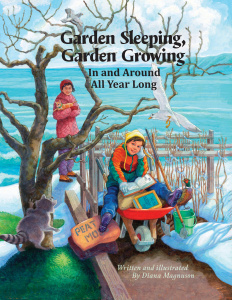

Garden Sleeping, Garden Growing: A Year-Long Love Letter to Natural Gardening

Click on the triangle below to listen to the interview!

I wrote Garden Sleeping, Garden Growing as a book that speaks from the garden’s point of view. Each spread represents a month of the year, and a short poem threads through the pages so children can follow the garden as it rests, wakes, flourishes, and settles back down for winter. July gets extra attention because that is when a northern garden hums with activity.

I wrote Garden Sleeping, Garden Growing as a book that speaks from the garden’s point of view. Each spread represents a month of the year, and a short poem threads through the pages so children can follow the garden as it rests, wakes, flourishes, and settles back down for winter. July gets extra attention because that is when a northern garden hums with activity.

Where the book came from

The seed of this book was my grandmother’s garden by Malax Lake in Minnesota. Those visits were my escape during a difficult childhood. Later, when I moved to the Upper Peninsula, a remarkable gardener named Noriko let me visit her plot monthly and told me stories about how things happened there. She gardened without pesticides and welcomed insects and animals into the community of the garden. Those memories formed the heart of the book.

Structure and illustration approach

Each month is a spread with an accompanying poem tailored more for young listeners than for adults. I wanted children to see food and gardens as part of a community: plants, insects, birds, mammals—all playing roles in a balanced ecosystem. Where appropriate, I included short, factual glosses right on the spreads so a child can point to a picture and learn without losing the flow of the story. Putting the glossary inside the book this way prevents the interruption of flipping to the back and losing the narrative thread.

Characters, reality, and a touch of fiction

Most of the book is true to the gardens I loved and observed, but I kept one fictional character: Delia, a little girl who helps Aunt Noriko. Delia is a nod to many children I’ve known—curious, practical, and delighted by blueberries. The rest of the cast are local creatures and gardening practices drawn from real life in the Upper Peninsula.

What kids learn from the book

- Seasonal rhythm: How a garden sleeps in winter and grows through spring and summer.

- Ecology at a glance: Animals and insects are shown doing what they do—pollinating, hunting, nesting—so children understand that not all insects are “bad” and that many creatures belong in the garden’s story.

- Practical gardening basics: Short facts explain ideas like crop rotation, soil health, and companion planting in simple language.

Challenges and the little gremlins

Handing a project from idea to finished book is rarely neat. I lived with this book idea for years. I joined a critique group of four other writers and artists, and their feedback was invaluable in shaping the text so the images in my head matched the words on the page.

But the biggest obstacle was my own hesitation—self-doubt, what I like to call the gremlins in your head. Those voices whisper that your writing or art isn’t good enough. One lesson I learned is simple but profound: keep making the work. Let the edits come later; let the joy of the work be first.

“Don’t let gremlins keep you from doing things you kind of want to do. When you write and do art, do it out of yourself and be true to yourself.”

Surprises and discoveries

Moving to the Upper Peninsula changed my sense of place. I learned a great deal about local insects and animals—everything from the stubbornness of deer to the stealth of snowy owls. Living here, I also discovered how much gardening is about community: neighbors sharing seeds, elders teaching techniques, and children learning that food grows out of a larger tapestry of life.

What I did right—and what I might do differently

I tried to stay true to my voice. There are countless children’s garden books, but no one else can tell this particular story the way I can. If I painted the book now, my style would likely be bolder and sillier in places, but the original book reflects who I was as an artist then. That honesty is the strength of the work.

Art, collaboration, and continued projects

Illustration is often solitary, but collaboration kept this project alive. My publisher was hands-on, and my critique group helped me see what needed adjusting. On other projects I’m exploring a blend of Northwest Coast Indigenous design with Celtic influences, working closely with community elders and cultural advisors to make sure the work is respectful and true. That collaboration has been one of the most meaningful parts of the process.

Takeaways for other creatives

- Keep creating: Painting or writing reconnects you with your deeper self and helps you through hard times.

- Find allies: A small critique group or an engaged publisher will catch things you miss and keep the project moving.

- Honor your voice: You cannot write or draw like anyone else. Your background and personality are your strength.

A short excerpt

I am garden. I rest. Under winter’s heavy chill, a blanket of white, I listen, half asleep, and grow in ways invisible to the eye. Tall trees surround me, their breath crackles in the cold. Hungry forest animals prowl, step, step, stepping over me. Their tracks cover my snow-belly drifts. Inside the cabin are my people who care for me, where a wood stove pings with warmth, and a bright seed catalog lies open on the table. Summer garden dreams begin.

Final words

If you have a garden project or a book idea, do the work. Let the gremlins be noisy but not in charge. Write and paint from your own experience and let revision be the time someone else helps you shape it. Gardening taught me patience, observation, and the joy of small miracles. Those lessons are my favorite harvests.