Sparks of the Revolution: Rediscovering Pre‑Revolutionary Boston and the Gift of Democracy

Click on the triangle icon below to listen to the Todd Otis interview

Why I wrote this book

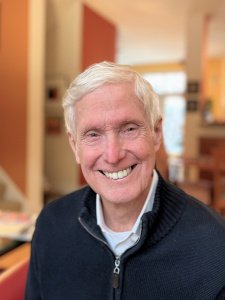

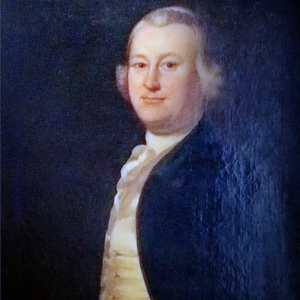

My last name is Otis. Growing up, I heard family stories about James Otis, the Patriot. When I retired, I decided to dig deeper. What I discovered was a life of brilliance and tragedy, and a gap in the historical record: Otis had burned his papers late in life. That made a different kind of book necessary. I chose historical fiction that adheres to documented facts but allows imagined dialogue and interior life where the record is silent. My book Sparks of the Revolution: James Otis and the Birth of American Democracy is the end result.

The courtroom that helped spark a revolution

One scene that drew me in was a Boston courtroom in February 1761. James Otis, once a king’s lawyer, stood up against the writs of assistance, the general warrants customs officers used to search homes, churches, and ships without particularized cause. The reaction in that crowded courtroom was electric. John Adams later wrote:

Otis was a flame of fire. American independence was then and there born.

Adams called that day the first scene of a long drama that would end in 1776. If a principal architect of the Revolution considered Otis pivotal, I felt compelled to tell that story.

Unsung actors who mattered

Most histories focus on familiar names. I wanted to illuminate the people who moved crowds, shaped opinion, and did the day-to-day work of resistance.

- Ebenezer McIntosh, a shoemaker, could assemble 2,000 to 3,000 citizens in a town of 15,000. He turned public fury into organized action.

- Mercy Otis Warren, a brilliant playwright and poet, wrote anonymously but powerfully. Her plays and poems were widely read in a literate Boston and helped shape public sentiment.

- Crispus Attucks, a dock worker of mixed indigenous and African ancestry, became a symbolic first victim of the growing conflict when he was killed during early clashes. His life and death remind us that the Revolution’s ideals would eventually need to expand beyond white property owners.

Key moments that changed everything

Most people remember the Boston Massacre of 1770 and the Tea Party of 1773. For me, 1768 matters just as much. The British sent 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers to occupy Boston, a town of about 15,000. Benjamin Franklin captured the danger in one line:

They will not find a rebellion, but they may cause one.

Occupation, crowd confrontations, funerals staged as political theater, and escalating violence created a pressure cooker. A child’s funeral drew tens of thousands. The pot was boiling long before shots were fired at Lexington.

How I researched and wrote the story

I spent two and a half to three years reading biographies, period histories, and contemporary newspapers. A daily online reader focused on 18th-century Boston helped with context, and traditional research filled in the rest. The arc of Otis’s life is remarkable: explosive legal brilliance, fierce public influence, and then a devastating decline after a violent attack by customs officials in 1769.

Writing took persistence. I set a modest goal, 500 words a day, four days a week. Multiple drafts, outside readers, and local editors helped shape the manuscript. Finding an agent proved the hardest part. Publishing finally happened after connecting with an independent press and several local advocates.

Voices and moments I kept returning to

Voices and moments I kept returning to

I wanted the book to feel alive. That meant getting inside personalities and public theater. Mercy Otis Warren’s lines capture the mood after the killings of the period:

That man dies well who sheds his blood for freedom.

Her anonymous plays were meant to inspire outrage and courage. I also paid attention to the interplay between public figures who could not be more different, such as the organizer Sam Adams and the wealthy, larger-than-life John Hancock. The combination of organizers, money, and public drama moved a community toward sustained resistance.

Lessons for today

The central lesson I took from deep study of 1760 to 1775 is that the Revolution gave us a radical idea:

People’s rights flow from a higher moral source, not from a monarch or autocrat. That concept was revolutionary in world history and remains the foundation of modern democracy.

But that gift was imperfect at the start. It began with white property owners and expanded over centuries to include women, people of color, and those without property. The work of broadening democracy continues. From the period I studied, three practical lessons stand out:

- If you treat people as enemies, many will become enemies. Polarization breeds conflict.

- Effective protest takes planning. The Boston Tea Party was carefully staged political theater, not spontaneous vandalism.

- Big ideals—freedom, dignity, truth, justice—can unite disparate groups and sustain long movements.

Who should read this book

I wrote Sparks of the Revolution: James Otis and the Birth of American Democracy for readers who care about the origins of democratic ideas, and for people who want history that feels immediate and human. If you are a new American, a young adult between 18 and 24, a social studies teacher, or a history buff interested in the lead up to revolution, this book is for you. I also hope it reaches readers across the political spectrum. The story of how rights were forged belongs to everyone.

Practical details and next steps

It took just over five years from first idea to publication. The process was rewarding and humbling. The most gratifying moments were getting published at all and hearing readers tell me the book brought the era to life for them.

I am already thinking about future projects, possibly exploring Abraham Lincoln’s life before the presidency. But for now, I remain focused on making the story of the Revolution feel accessible and meaningful for readers today.

Parting thoughts

Keep faith in democratic institutions and remember that individual participation matters. Protecting and extending the gift of democracy requires work, planning, and the willingness to stand up for ideals that bring people together.

Write, read, and stay engaged. Democracy depends on active citizens.